Cheetah Confiscations: A Frontline Perspective

-

- by Dr. Ashley Marshall September 5, 2022

CAZA

This article was originally written for publication by Canada’s Accredited Zoos and Aquariums

Author: Ashley Marshall, BSc, DVM

Contributor: Nathalie Santerre

Editor: Laurie Marker, BSc, DPhil Zoology

The call came on a Saturday, alerting us to a group of stolen cheetah cubs. It had barely been a month since the last large confiscation of 15 young, traumatized individuals, eight of which succumbed to severe trauma, malnutrition, and stress.

A team comprised of a vet, vet technician, operations manager, special protection unit member, and translator assembled necessary animal care and medical supplies to start the day-long journey to reach the cubs. They met with with the regional coordinator of the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change (MoECC) in a secure location.

The nine confiscated cheetah cubs weighed between 0.5 and 2 kg. They were given to the Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF) team for initial assessment and stabilization which included rehydration, active warming, parasite control and ensuring their safety and security. After a night in a local hotel, the team transported them to CCF Somaliland headquarters where the team on the ground was ready to receive them.

The accumulated stress on the cubs eventually became apparent. When the cheetahs arrived at the clinic, one individual crashed immediately due to low blood sugar. This cub was also demonstrating abnormal neurological behaviour. The first hours were spent providing critical care to this individual, which included dextrose and fluid supplementation, assessing the little blood we could access, and performing CPR twice, after which she went into respiratory arrest and died.

Without a moment to breath, the team quickly pivoted to assessing the remaining cubs. Physical assessments were performed and physiological data including measurements, blood, faeces, parasites, body condition scores and weights were recorded. Diets were calculated based on estimated age, body condition score and current weight. Unsure of the length of their imprisonment, malnourishment, and potential starvation, significant caution was taken when introducing high quality nutrition, to prevent potentially fatal refeeding syndrome and fatty liver disease.

The smallest and youngest were relocated to staff housing for around the clock observation and bottle feeding every 2-4 hours. The larger and estimated older cubs were left in quarantine near the clinic; staff were stationed with them the first night for observation and frequent feeding. Although traumatized, the cubs appeared to be settling in, sleeping, and grooming together in hay for warmth and comfort and ravenously eating the meager portions provided.

The following day, the cubs appeared calm and stable. However, by 4pm, one of the smaller cubs was fading. His blood sugar was dropping and he was becoming weak. Intravenous access was attained, and fluids supplemented with dextrose were provided. Antibiotics were given in case of infection or sepsis. Despite our best efforts and intensive care, he declined overnight and started to show abnormal neurological signs. After a long night of constant monitoring the team elected to humanely euthanize.

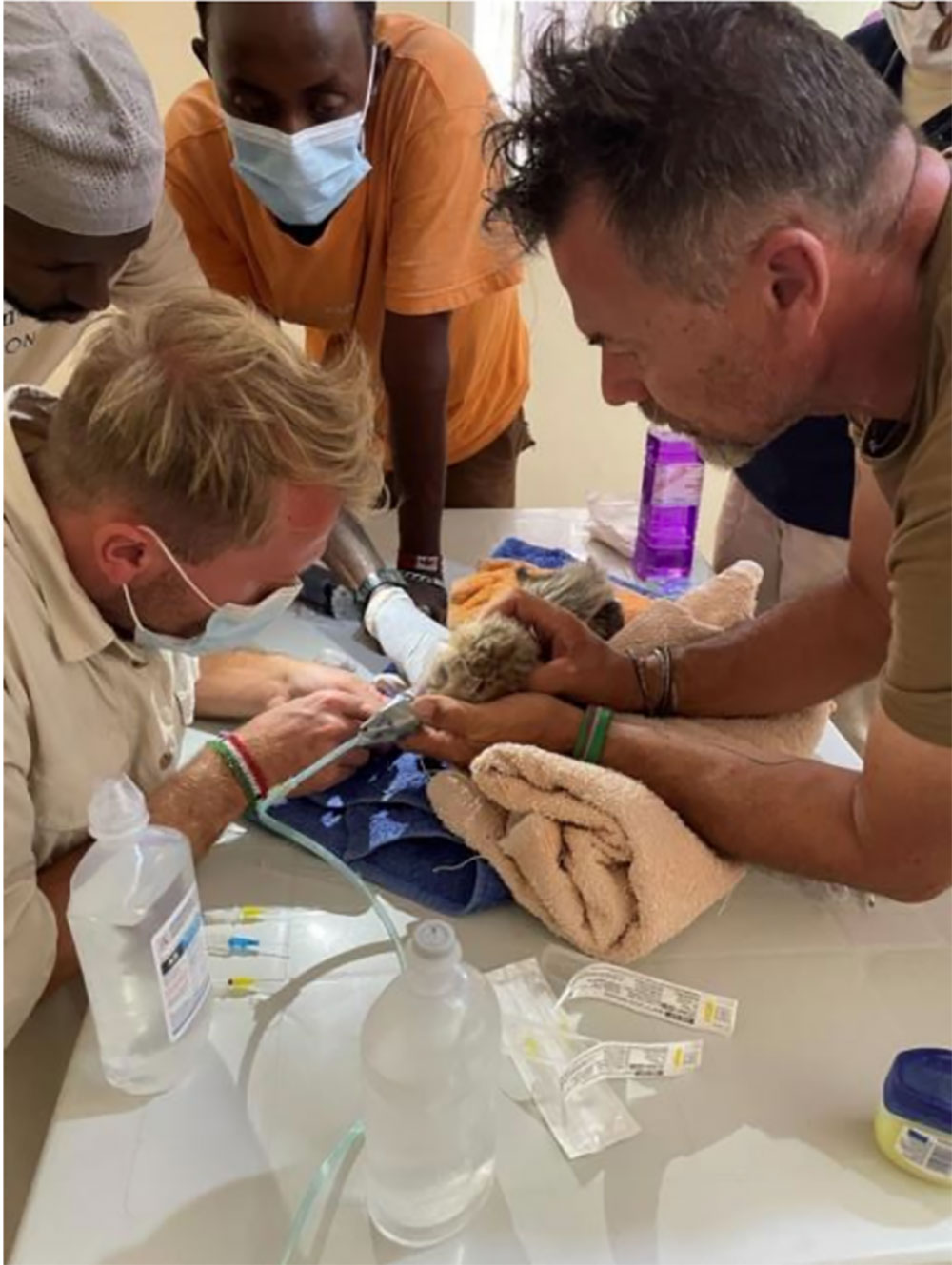

Hoping we were through the worst, we continued to care for the remaining seven cubs. By midday on day three, a third cub started to show weakness. Her gums were pale and her breathing was rapid and shallow. Bloodwork showed generalized inflammatory changes and severe anaemia. A healthy (sub)adult male in our resident population was selected as a blood donor and he we sedated to donate blood. While the head vet managed this procedure with the dedicated animal care staff, the secondary vet ran the sample to the cub and began the transfusion. Antibiotics were also started to reduce the risk of any infection.

The cub responded well to the donated blood and seemed to perk up the next day. She was provided vitamin supplementation, medications to support intestinal health and motility and continued to receive around the clock care. Sadly, our little girl declined 48 hours after receiving her first transfusion, so a second transfusion was administered.

Over the proceeding night she declined further; she was unable to maintain her blood sugar levels and began to show familiar neurological decline. At this point, she was passing soft black stools and morning blood assessments indicated sepsis; after reviewing the case with the greater veterinary and animal care teams, humane euthanasia was elected. She was a sweet little female of about three to four months and fought for five days before finally losing her battle.

Over the past four years, since CCF set up their three Safe Houses, this, sadly, has become a regular occurrence. The cubs are in such bad condition when they reach us, mostly from malnourishment, a condition called re-feeding syndrome, that many do not survive. Like humans suffering from malnourishment, their bodies are unable to metabolize the food they receive, even if only small amounts of food are given at any time. Of the remaining six cubs, five have done well. Some graduating from frequent bottle feeding, then from mince to chunk to bone meat, the cubs continue to put on weight and condition. They are well adjusted young cheetahs who require ever evolving care in terms of diet adjustments, training and enrichment, and preventative medical care such as vaccines, deworming, microchipping, body weight and condition assessments.

The illegal wildlife trade is not faceless. Victims suffer immeasurable mental and physiological stress. They are imprisoned, sometimes chained, or tied up and neglected. Not all survive, and the ones that do often maintain a lifelong fear of humans. We at CCF Somaliland are reminded of this every day as we care for these rescued survivors.

Currently, CCF Somaliland is home to 85 resident cheetahs, with annually increasing numbers of confiscations. CCF director Dr. Laurie Marker tackles has a multifaceted approach to tackling this seemingly insurmountable challenge.

Somaliland is the hub for the movement and trade of this endangered species and CCF works not only on front line rescue efforts, but is also actively involved in education, community engagement, policy, and enforcement.

Working closely with the MoCC, CCF is building an 800-hectare Cheetah Rescue and Conservation Center (CRCC) within Somaliland’s first National Park to provide more space for the rescued cheetahs to live a more natural existence. The CRCC is currently under construction with staff housing and a veterinary clinic. Large camps are being fenced to house the current 85 cheetahs in a natural habitat. We hope to have the cheetahs moved to the CRCC by early 2023.

Phase Two will include an Education and Training Centre to educate, train, and engage with the community at large to decrease and hopefully end the illegal wildlife trade. This trade not only endangers the species, but also inflicts pain and suffering on young and defenceless cheetahs.

CCF is looking for partners to help support the building of the Education Centre and welcomes Zoo Keepers, Veterinary Technicians, and Veterinarians to volunteer or join us as staff. CCF is working on stopping the supply and demand sides of the illegal wildlife pet trade by building awareness. In the Horn of Africa, Somaliland and Ethiopia, CCF has been active in community engagement and awareness building, along with training of police and wildlife task force to stop the trade. In the Middle East, CCF has been developing relationships at the highest levels to stop the demand. It will take time, but CCF is working on many levels to deal with this crisis.

CCF in an international non-profit organization with field bases in Namibia and Somaliland, and volunteer support organizations around the world. CCF Canada welcomes members and volunteers to help spread the word and to help support the work of CCF in their efforts to develop and implement solutions.

Related Reading

-

June 12, 2024

Continuation Assigned Task is National Obligation -

March 8, 2023

Support the Cheetah Rescue and Conservation Centre