What is a Studbook and Why is it Important for Conservation?

-

- by Heather Taft January 24, 2017

Conservation is an interdisciplinary effort combining subjects that are widely divergent – from genetics for assessing diversity of populations to information technology for inventing and sharing new methods of data analysis, among many others. It is also a discipline that has no defined national boundaries since the species that need conservation do not stay within the invisible boundaries humans have used to define nations. However, enacting conservation efforts does require knowledge of nations inhabited by the species, and who within those countries work with the species. This allows conservation efforts to be coordinated without wasting precious time repeating work that has already been done.

A large portion of conservation work focuses on animals that live in the wild, but captive animal populations have also become important for saving species. The Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) accreditation process mandates that zoos participate in conservation work that benefits wild populations. Zoos conduct conservation research that is focused on cataloging genetic material, implementing captive breeding programs to increase the number of individuals of endangered species, and they have programs that education the public about conservation. Research has also focused on reintroduction programs, where captive animals have been released into the wild. However, maintaining healthy captive populations is critical for this next step, along with habitat restoration, and reducing the issues that caused the specie’s numbers to decline so that reintroduction could be a success.

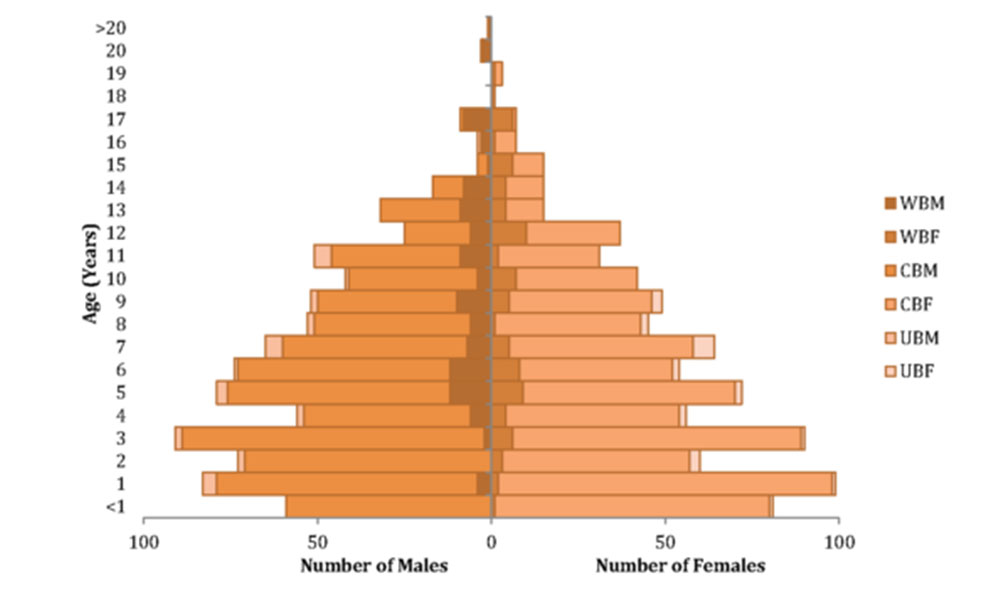

Collaboration between captive animal managers around the world is important to sharing best practice for animal care and captive breeding. To facilitate good management, a registry of the captive individuals of a species is a useful tool to assist in population management. In the zoo world, this registry is known as a studbook and monitors births, deaths, parentage, individuals acquired from the wild, their location, and any transfers of individuals. Many endangered and vulnerable species have studbooks to coordinate management efforts. Dr. Laurie Marker is the Studbook Keeper for the International Cheetah Studbook. Every year since 1988 Dr. Marker publishes a revised version of the studbook – that’s 28 years of studbook data.

The International Cheetah Studbook for 2015 was published in November 2016. The studbook has the purpose to register “all cheetahs in the world held in both zoological and private facilities and providing information about existing animals by publishing the studbook contents thus creating the preconditions for selecting breeding animals.” Managers of facilities that house cheetahs use the studbook to optimize breeding efforts by ensuring that cheetahs paired for breeding are not related.

Cheetahs are a species that are already genetically compromised, therefore understanding their captive pedigree is important for appropriate breeding and to prevent inbreeding (where closely related animals breed together). Inbreeding among related individuals is problematic because there are many genetic diseases that hide in DNA. Cheetahs, like humans, receive two copies of their genes from their parents – one from their mother and the other from their father. Different versions of the same gene are known as alleles. A good example of alleles for humans is shown using blood type: if a mother passes on an allele for type A blood to her offspring, and the father passes on an allele for type B blood, the resulting offspring will have one type A allele and one type B allele producing a type AB child.

Not all alleles are displayed equally as shown in the AB blood type example though. There are dominant and recessive alleles. Dominant alleles are always expressed. Recessive alleles are only expressed when they occur in pairs, having been received from both parents. This means harmful recessive alleles occurring in single copies can be passed from parent to offspring without anyone knowing or there being any negative effects. Only individuals with two harmful recessive alleles would be disadvantaged, potentially leading to poor health and an earlier death.

The studbook allows managers at breeding facilities to identify cheetahs that may share the same alleles by determining common ancestry. Two individuals who have the same recessive allele have a 25% chance that both of those alleles could be passed on to their offspring – giving that individual two copies of a potentially harmful allele. In worst case situations two copies of harmful alleles results in miscarriages, or death of cubs shortly after birth. In other instances, the result could be debilitating diseases that may cause death at a later stage, reduced quality of life, or sterility. The best options to reduce issues associated with harmful alleles is to try to ensure the individuals who share these alleles do not reproduce with each other.

For some animals, reintroduction remains an elusive goal due to continuing habitat loss, human animal conflict, and illegal hunting/wildlife trade. While scientists work in the field to revitalize the wild habitat, it is important that captive animals be maintained to maximize the retention of genetic diversity, and to increase the chance of success for any animals that are returned to the wild in the future. While it is the hope of all who work in conservation that wild populations will continue to increase, animals that are designated “extinct in the wild” have made comebacks due to concerted efforts and zoo breeding programs. Black-footed ferrets were thought to be extinct until a small colony was discovered in the late 1980’s and 18 individuals brought into a breeding program run by United Stated Fish and Wildlife and the Smithsonian’s National Zoo. While the black-footed ferret is still considered “Endangered” on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Red List of threatened species, their wild populations continue to grow.

With the release of the study Disappearing Spots: The global decline of cheetah Acinonyx jubatus and what it means for conservation pertaining to the decline of the adult cheetah population to less than 8,000 individuals, it is even more imperative that we keep detailed genetic records of each and every cheetah in captivity. The captive population is important to the species as a whole – it is a genetic backup for the wild population.

Featured photo by Steven Shpall

Related Reading

-

August 27, 2025

Sniffing Out Stories with the Scat Detection Dog Team