Project Cheetah: Patience Paves the Path for Ecological Success

-

- by Malee Oot July 30, 2024

Article Summary: Spatial Ecology of Cheetahs in India: Complexities beyond extrapolation from Africa

Authors: Cristescu B., Jhala Y. V., Balli B., Qureshi Q., Schmidt-Küntzel A., Tordiffe A., van der Merwe V., Verschueren S., Walker E., Marker L. L.

Reintroduction is a well-established strategy for restoring individual species or populations to regions or ecosystems they have historically occupied. One of the most prominent examples has been the reintroduction of gray wolves from Canada to Yellowstone National Park in the United States during the summer of 1995 – after an absence of nearly 70 years. Over time, these species reintroductions – particularly the restoration of large carnivores – can have a significant ecological impact, enhancing the functioning of ecosystems and boosting biodiversity.

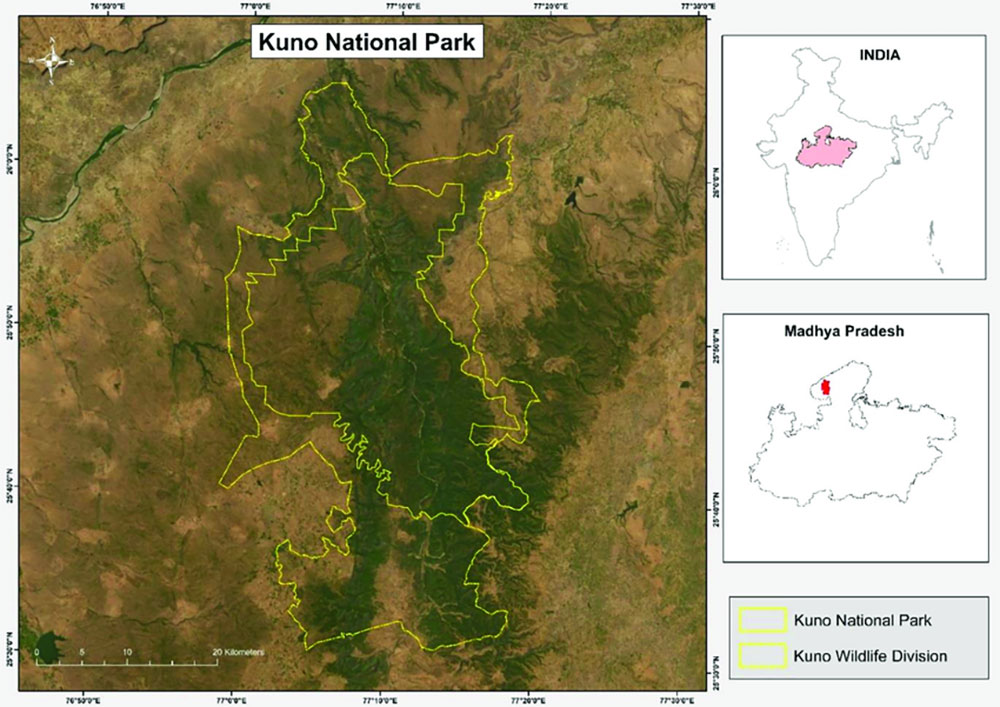

Recently, a high-profile reintroduction effort has involved the return of cheetahs to India. Once widespread in the country, cheetahs were driven to extinction in India by the middle of the 20th century, primarily due to offtake from the wild and conflict with humans. To facilitate the restoration, during 2022 and 2023, wild cheetahs were translocated from Namibia and South Africa to India for release in Kuno National Park, located in the state of Madhya Pradesh, approximately 320 kilometers (200 miles) south of Delhi. While Project Cheetah has received public and political support, the initiative has catalyzed scientific debate – especially given the scarcity of information on cheetah ecology in India.

A significant portion of the scientific debate surrounding Project Cheetah relates to predictions about how the translocated cheetahs will potentially utilize their new habitat in India. For example, a scientific paper published last year outlined concerns about cheetah movements within Kuno National Park, based on studies of cheetah spatial ecology in Africa. In this case, researchers based their behavioral predictions on data collected in the Namibian Kalahari savannah and the Serengeti in Tanzania. While these two African ecosystems are distinct, both are relatively flat with predominantly open vegetation. By comparison, Kuno National Park features a more densely forested landscape perforated by large waterways, which could also function as a barrier to dispersing cheetahs.

Still, individual cheetahs at Kuno National Park are expected to test the permeability of natural barriers and to make exploratory movements during the early stages of their release. Project Cheetah has protocols in place to address these challenges, including monitoring translocated cheetahs with GPS radio collars, and forming rapid response teams with the capacity to capture and return roaming cheetahs to the national park. Public information and awareness campaigns combined with compensation schemes to address livestock losses, have also been utilized to increase tolerance levels toward translocated cheetahs. At the finalization of this manuscript, there were no cheetah mortalities due to conflicts with humans, domestic dogs, or leopards.

While the territorial behavior of cheetahs is complicated – dynamics between males and females influence movement patterns. Namely, adult males may adapt territorial behavior to increase their chances of encounters with females for mating – and therefore, the presence of females can influence the way male cheetahs use the landscape. Preliminary data suggests the territorial behavior of male cheetahs can be manipulated by the presence of females – including translocated females temporarily held in a boma, or even just the strategic placement of female scats at marking sites. However, data on the influence of female presence on the territorial behavior of male cheetahs at Kuno National Park is still being studied.

Another concern raised about the return of cheetahs to India has been cheetah densities as related to available space in India. Since cheetahs are typically a wide-ranging species, population densities tend to be low. However, cheetah ecology in Kuno National Park may differ from the African ecosystems used as the basis of current cheetah space use predictions. Ultimately, the distribution of cheetahs over the landscape is driven by the movement decisions of individual animals, which are determined by a variety of factors, primarily the availability of prey, suitable habitat for hunting, perceived threats, competition for resources, especially from other large predators, and the availability of natural features for territorial marking.

One of the overarching challenges for Project Cheetah is the need for baseline data on cheetah ecology in India – a scientific gap driven by the fact that cheetahs disappeared from the country more than a half century ago. At Kuno National Park, the reintroduction timeline – with cheetah releases staggered over time – allows for the collection of data and lessons learned, enhancing the base of ecological knowledge for each new cheetah arrival. Ultimately, major restoration initiatives, such as Project Cheetah, need time.

Related Reading

-

February 27, 2026

In the Footsteps of the Kenyan Cheetah: A Genetic Odyssey -

August 27, 2025

Sniffing Out Stories with the Scat Detection Dog Team