About Cheetahs

A Wild Diet

Cheetahs rely on prey species that have adapted speed and agility to evade them, such as Thomson’s gazelles, impalas, and other small to medium antelopes. They will also hunt hares, birds, rodents, and occasionally the calves of larger herd animals.

Wild prey is strongly preferred. Livestock is rarely targeted except by cheetahs that are young, old, or injured, and even then the animals taken are often already weak or vulnerable. Housing livestock in kraals and using non-lethal protection methods have been shown to greatly reduce losses.

Feed a Cheetah

Feed the Fastest Cat on Earth

Across our centres in Namibia and Somaliland, cheetahs eat between 2 and 4 pounds of meat each day, adding up to thousands of pounds every week. In the wild, they hunt gazelles, impalas, and other swift prey, but at CCF we provide balanced meals that keep them strong and thriving.

With a gift of just $5, you can buy a cheetah a meal and help us continue protecting this endangered species.

The Cheetah’s Wild Life

Cheetahs progress through three life stages: cub (birth to 18 months), adolescence (18–24 months), and adulthood (24 months and older).

Cubs (Birth to 18 months)

Cheetah cubs are born after a 93-day gestation. Litters usually contain 1–6 cubs, though up to 8 have been recorded. Mortality is high, especially in protected areas where lions, hyenas, and other predators are common. In some regions, as many as 90% of cubs do not survive.

Adolescents (18 to 24 months)

Between 18 and 24 months, young cheetahs learn to hunt and begin living more independently. During this period, survival depends on successfully transitioning from dependence on their mother to securing prey on their own.

Adults (24 months and older)

In the wild, cheetahs live an average of 10–12 years. Adult males often have shorter lifespans, averaging around 8 years, due in part to conflicts with rival males over territory. High adult mortality is one of the biggest factors limiting wild cheetah population growth.

Vocalizations

Unlike the other “big cats” — lions, tigers, leopards, and jaguars — cheetahs cannot roar. Instead, they growl when threatened, chirp or make birdlike calls to communicate, and bark in social interactions. Cheetahs are also one of the few cats that can purr continuously while both inhaling and exhaling.

Purring

Moan/Spit

Chirping

Growling

Growl/Chirp

Physical Characteristics of Adult Cheetahs

Adult cheetahs typically weigh between 75 and 125 pounds. Their bodies measure 40 to 60 inches from head to hindquarters, with tails adding another 24 to 32 inches — making their total length up to 7.5 feet. At the shoulder, cheetahs stand about 28 to 36 inches tall.

Males are slightly larger than females, with bigger heads, but the differences are subtle compared to other big cats like lions.

Cheetahs have a slim build, narrow waist, and deep chest. Their large nostrils, lungs, and heart, along with a highly efficient circulatory system, supply oxygen rapidly during a sprint.

With long legs and a uniquely slender frame, the cheetah differs from all other cats and is the only member of its genus, Acinonyx. Its specialized body structure is what allows it to reach the extreme speeds that make it the fastest land animal.

Markings

A cheetah’s coat ranges from light tan to deep gold and is covered with solid black spots, unlike the open rosettes seen on leopards or jaguars. This spotting pattern is one of the quickest ways to identify a cheetah.

Distinctive black “tear stripes” run from the eyes to the mouth. These may reduce glare from the sun and help cheetahs focus on prey at long distances, functioning much like the crosshairs of a scope.

The tail ends in a bushy tuft marked by five or six dark rings. These patterns provide camouflage and may also serve as signals, helping cubs follow their mothers through tall grass. The tip of the tail varies among individuals, ranging from white to black.

Cheetah Appearance – Quick Facts

🐆 Coat: Light tan to deep gold, covered with solid black spots (not rosettes like leopards or jaguars).

👀⚫ Tear Stripes: Black lines from eyes to mouth reduce sun glare and help focus on prey.

〰️〰️〰️ Tail: Bushy with 5–6 dark rings; used for camouflage and signaling. Tail tips vary from white to black.

Built for Speed

The cheetah is the fastest land animal and Africa’s most endangered big cat. Built for speed, it can accelerate to more than 110 km/h (70 mph) in just over three seconds, covering strides up to seven meters long. Its flexible spine, long legs, narrow frame, and balancing tail all contribute to its incredible sprinting ability. Specialized muscles give the limbs a wider swing, boosting acceleration.

Cheetah foot pads are hard and less rounded than those of other cats, acting like tire treads for traction during sharp turns. Their short, semi-retractable claws resemble a dog’s more than a cat’s, working like track spikes to grip the ground and increase speed.

Fast and Flexible

The cheetah’s spine is uniquely flexible, acting like a spring that powers each stride. Its long, muscular tail works like a rudder, counterbalancing body weight and swinging side to side to stabilize sharp turns during high-speed chases.

Unlike most cats, a cheetah’s shoulder blades are not fixed to the collarbone, which allows the shoulders to move freely. At the hips, the joints pivot widely so the rear legs can stretch far apart when the body is fully extended. Together, this hip and shoulder flexibility produces an exceptional stride length of 6–7 meters (about 21 feet), with four strides completed every second. During each stride, the cheetah is airborne twice: once when fully extended and once when the legs are tucked beneath the body.

Cheetah Cubs

At birth, cheetah cubs weigh just 8.5 to 15 ounces and are blind and helpless. Their mother grooms them patiently, purring softly while keeping them warm and safe. Within a day, she must begin leaving them briefly to hunt, making this the most vulnerable stage of their lives.

For the first six to eight weeks, cubs remain in a secluded nest. During this time, the mother regularly moves them from one hiding place to another to reduce the risk of discovery by predators. She raises her cubs alone, caring for them for up to 18 months.

At about six weeks of age

As cubs grow, they begin following their mother on her daily hunts. During these months, she cannot move far or fast, and cub mortality is highest — fewer than one in ten survive. Most losses are due to predation by lions, hyenas, or eagles, though injuries also take a toll. This is also when cubs begin learning essential life skills.

Young cubs are covered with a thick silvery-grey mantle along their backs. This mantle provides camouflage by mimicking the appearance of a honey badger, a notoriously aggressive animal. The mimicry may help deter predators, but the mantle is shed by about three months of age.

Between four to six months of age

Cheetah cubs are highly active and playful. They climb trees to practice balance, sharpen coordination, and use their extra-sharp semi-retractable claws to grip the bark of tall “play trees.” Play with siblings helps build strength and agility, preparing them for life as hunters.

Learning to hunt is the most critical skill for survival. By about one year of age, cubs begin to take part in hunts alongside their mother.

At about 18 months of age

Eventually, the mother and cubs separate. Though not yet fully skilled hunters, adolescent males and females remain together for several months to continue practicing. As the young females begin cycling, they are courted by dominant males, who drive away their brothers.

Male Coalitions

As female siblings reach sexual maturity, they leave the group to live largely independent lives. Male siblings, however, remain together for life in groups known as coalitions. Living in a coalition increases hunting success and provides defense against rival predators.

When separated from their sisters, young males may roam for years before establishing a territory. They can travel hundreds of miles, often displaced by stronger coalitions, until they eventually settle in an area of 15 to 30 square miles.

In cases where young cheetahs are orphaned and raised in rehabilitation, non-related individuals can be paired together. Once released, these artificially formed coalitions often stay intact throughout their lives, mirroring the natural bonds between brothers.

Mating

Female cheetahs lead mostly solitary lives, except when raising cubs. Unlike males that defend fixed territories with their coalition, females travel across “home ranges” that often overlap the territories of several male groups. The size of a female’s range depends on the availability of prey, when prey is scarce or widely dispersed, her range expands.

Female estrus is irregular and influenced by environmental cues, particularly the proximity and scent markings of males. This unpredictability makes breeding cheetahs in captivity challenging. Estrus can last up to 14 days, during which females may mate with multiple males. When a female is receptive, males that encounter her will remain with her for up to three days, mating repeatedly throughout the day. Within a coalition, there is no single dominant male that monopolizes breeding opportunities, all members will mate.

Genetic Diversity

During the last Ice Age, cheetah numbers collapsed to only a small group of survivors. This population bottleneck caused a dramatic loss of genetic diversity, leaving today’s cheetahs unusually uniform. In fact, experiments have shown that reciprocal skin grafts between unrelated cheetahs are often accepted because of their genetic similarity, particularly in their major histocompatibility complex (MHC).

Genetic diversity is critical for populations to adapt to environmental changes and survive unexpected challenges. Human-driven habitat loss and fragmentation increase isolation, which leads to inbreeding and further reduces genetic variation.

Low genetic diversity has been linked to several health problems in cheetahs, including poor sperm quality, focal palatine erosion, greater susceptibility to disease, and physical deformities such as kinked tails. These impairments are seen in both wild and captive populations.

Feed a Cheetah

Feed the Fastest Cat on Earth

Across our centres in Namibia and Somaliland, cheetahs eat between 2 and 4 pounds of meat each day, adding up to thousands of pounds every week. In the wild, they hunt gazelles, impalas, and other swift prey, but at CCF we provide balanced meals that keep them strong and thriving.

With a gift of just $5, you can buy a cheetah a meal and help us continue protecting this endangered species.

Hunting

Cheetahs are visual hunters and, unlike most other big cats, they are diurnal — active mainly in the early morning and late afternoon. They often climb termite mounds or tall “play trees” to gain a better vantage point for spotting prey on the horizon.

The hunt follows a sequence: detection, stalking, the chase, tripping or capturing the prey, and finally a suffocating throat bite to make the kill.

Activity

Although cheetahs can reach remarkable speeds, they cannot sustain a chase for long. Prey must be caught within about 30 seconds, as maximum speed can only be maintained briefly.

Outside of hunting, cheetahs spend much of their time resting. They avoid the heat of midday by sleeping in shaded areas, often beneath large trees. True to their diurnal nature, they are most active during the cooler hours of morning and evening, and they do not hunt at night.

Role in the Ecosystem

The cheetah plays a vital role in the savanna ecosystem. Though one of the most efficient hunters, its kills are often taken by larger carnivores or groups of predators. Like all predators, cheetahs help regulate prey populations by removing weak and old individuals, keeping herds healthy and balanced.

By limiting overgrazing, predators indirectly support plant communities and maintain ecosystem stability. Without predators such as the cheetah, Namibia’s savannas would look very different — and the ongoing trend toward desertification would likely accelerate.

Species Then and Now

Relatives of the modern cheetah had worldwide distribution until about 20,000 years ago, when the world’s environment underwent dramatic changes during the Great Ice Age. Only a handful of individuals remained.

The population of cheetahs rebounded. Up until ~10,000 years ago their range spread across the entire African continent (minus the Congo Basin and the Sahara Desert) and into Asia from the Arabian Peninsula to eastern India. Today, cheetahs are found in only 9% of their historic range and are functionally extinct. Once found throughout Asia and Africa, today there are fewer than 7,100 adult and adolescent cheetahs in the wild.

Protected Status

Currently, cheetahs are listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. In Namibia, they are a protected species. Under the Endangered Species Act in the United States, they are considered Endangered. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) lists them as an Appendix 1 species. Most wild cheetahs exist in fragmented populations in pockets of Africa, occupying a mere 9 percent of their historic range. In Iran, fewer than 50 Asiatic cheetahs (a sub-species) remain.

The largest single population of cheetahs occupies a six-country polygon that spans Namibia, Botswana, South Africa, Angola, Mozambique and Zambia. Namibia has the largest number of individuals of any country, earning it the nickname, “The Cheetah Capital of the World.” More than 75 percent of remaining wild cheetahs live on rural farmlands alongside human communities.

Cheetahs in Captivity

In captivity cheetahs can live from 17 – 20 years. In countries across Africa, like Namibia, it is illegal to capture and take live cheetahs from the wild. Also in the majority of African countries, like Namibia, it is illegal to keep cheetahs under private ownership or as pets. Cheetah Conservation Fund and other Africa-based NGOs keep populations of injured or orphaned animals in captivity as part of rehabilitation and rewilding efforts.

Suitability for release is dependent on:

- the age of the individuals when they became orphaned

- the degree to which human intervention was required for their survival

Very young and extremely ill animals will have greater degrees of contact with human caretakers. Survival in the wild depends on an aversion to humans and avoidance of human populations. Cheetahs that require hand-rearing and prolonged medical treatment do not possess an adequate fear of humans for life in the wild, especially when their territories are increasingly likely to be shared by human settlements.

Zoos and Conservation

Accredited zoos around the world participate in captive breeding programs that track the genetic suitability for mating pairs. Accreditation criteria differs between accrediting organizations. Accreditation in most cases requires that zoos holding captive cheetahs must support conservation work. Cheetah Conservation Fund lists the zoos that fund our conservation work here.

Cheetah Conservation Fund manages the International Cheetah Studbook for captive cheetah populations.

Specialized Conservation Needs

As with all other species fighting extinction, the problem facing the cheetah is complex and multifaceted. However, most of the reasons for the cheetah’s endangerment can be grouped into three overarching categories:

- human-wildlife conflict,

- loss of habitat and loss of prey,

- poaching and illegal wildlife trafficking, with cubs being taken from the Horn of Africa and smuggled into the exotic pet trade, primarily in the Gulf States.

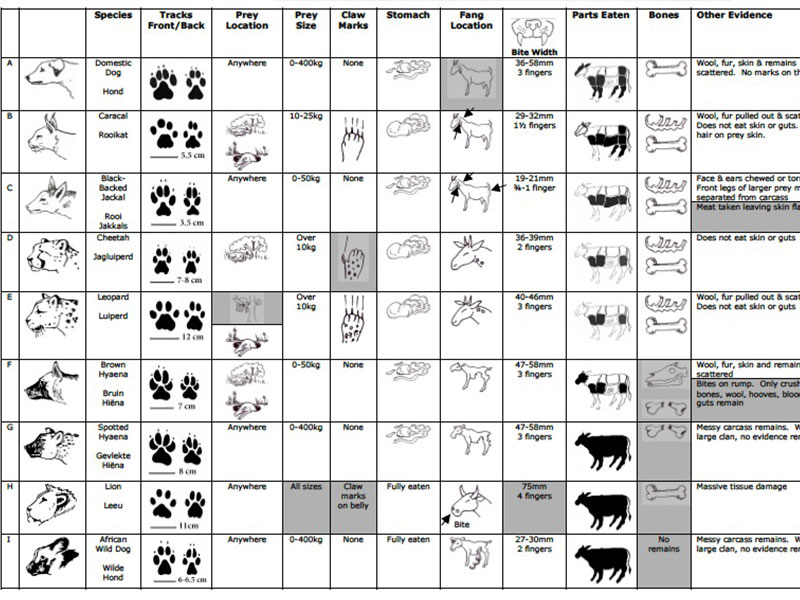

Human-Wildlife Conflict

Unlike other large cats and pack predators, cheetahs do not do well in wildlife reserves. These areas normally contain high densities of other larger predators like the lion, leopard, and hyena. Predators such as these, compete with cheetahs for prey and will even kill cheetahs given the opportunity. In such areas, the cheetah cub mortality can be as high as 90%. Therefore, roughly 90% of cheetahs in Africa live outside of protected lands on private farmlands and thus often come into conflict with people.

When a predator threatens a farmer’s livestock, they also threaten the farmer’s livelihood. Farmers act quickly to protect their resources, often trapping or shooting the cheetah. Because cheetahs hunt more during the day, they are seen more often than the nocturnal predators which contributes to a higher rate of persecution on the cheetah.

Human-wildlife conflict

Learn more about CCF’s efforts to mitigate human-wildlife conflict

Habitat Loss

Cheetahs require vast expanses of land with suitable prey, water, and cover sources to survive. As wild lands are destroyed and fragmented by the human expansion occurring all over the world, the cheetah’s available habitat is also destroyed. Available habitat is fragmented, and degraded reducing the number of animals an area can support. Numerous landscapes across Africa that could once support thousands of cheetahs now struggle to support just a handful.

Illegal Wildlife Trade

In many parts of the world there are strong cultural associations to keeping cheetahs as companions. There is a long history of the practice and it is commonly seen in ancient art.

In contemporary times, cheetahs are still viewed as status symbols. Though cheetah ownership and exotic pet ownership has been outlawed in many countries, there is still a high demand for cheetahs as pets. Cubs are illegally captured from the wild and only one in six survives the journey to a potential buyer.

Illegal Wildlife Trade

Learn more about CCF’s efforts to end the illegal trade in cheetahs across the species range.