Cheetahs and Alternative Energy in Africa: The Canadian Engineering Connection

-

- by Eric Kyfiuk September 9, 2014

To say I didn’t know what to expect when I arrived in Windhoek, capital of Namibia – one of the world’s most sparsely populated countries and home to more cheetahs than anywhere else – is a real understatement.

My first night was spent hungry and jet lagged in a dusty tent to which my over-booked hostel had relegated me because “TIA” (This Is Africa).

But things have improved for me ever since that first night of unexpected backyard camping. From making friends to making mistakes, from leading a youth camp to leading a safari, from managing a factory to managing a flood, my time in Africa has been a non-stop adventure.

I came to Namibia in October 2013 to assume management of the Cheetah Conservation Fund’s Bushblok factory, having completed my degree in Mechanical Engineering at the University of Victoria in British Columbia earlier that year.

I was drawn to southern Africa for the challenge, the unfamiliarity, and the sun. My predecessor at the factory, a friend and fellow engineering graduate from UVic, connected me to the project after he was introduced to it through his work in Africa with Engineers without Borders.

Cheetah Conservation Fund started “CCF Bush” in 2001 to restore cheetah habitat in the savannah. Sparsely-treed plains once allowed cattle, game and predators to thrive in Namibia, but 12-14% of the country is now covered with dense, invasive thorn-bush.

The overgrowth is due to a number of things including overgrazing of competing grasses by cattle, removal of large browsers such as elephants, and suppression of bush fires.

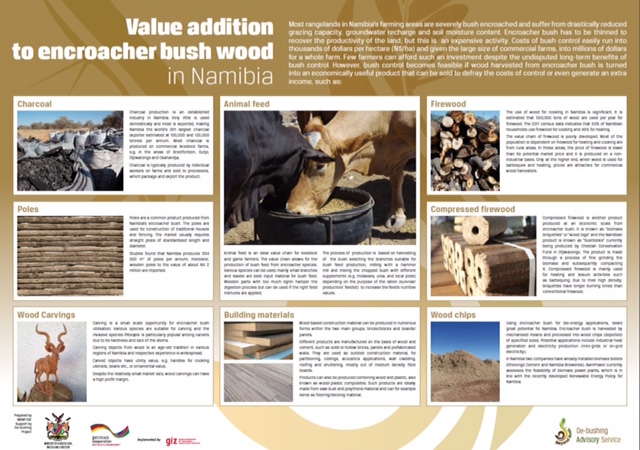

The project seeks to thin the bush both sustainably and economically and is monitored by the Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC). Invasive species are removed and a healthy number of trees are left behind in order to encourage a natural vegetation balance. Plants that are harvested are dried, chipped and transported to the factory where they are processed into Bushblok

This compressed biomass briquette is a carbon-neutral source of alternative energy and is gaining popularity in parts of Namibia, South Africa and the UK. The initiative is only a pilot project meant to stimulate a sustainable industry in Namibia; it doesn’t have the economies of scale it needs to be profitable yet.

When I arrived at the factory, I saw that many areas needed improvement. Starting a new industry and proving technology for local conditions is difficult in any country, but it is especially hard in dusty, remote, developing Namibia.

Canadians who work abroad are known for our insistence on safety – a responsibility which is signified by a special ring that is given to every Canadian BEng. The ring has been a fitting symbol (pun intended!) for my work in Africa. In a follow-up article I’ll explain how my time here has been most beneficial in this area.

When a pilot project doesn’t have the finances to procure a lot of custom-built equipment, problems can only be solved through innovation, improvisation and experimentation. And when devising systems from scratch, it’s vital to have a thorough engineering background.

I had the advantage of a great university and co-op education which made it possible for me to diagnose shaft failure, design new machinery, predict overall system weaknesses and form a vision for improvements. Even my elective courses have been brought to bear: In my final year of engineering, I took a course that studies biological systems through a mechanical lens. This background led me to theorize about the way physical characteristics of savannah plants might relate to their chemical properties as biomass.

Canadians at home might be interested to know that when you go abroad with the right combination of respect, resourcefulness, training and grit, you can effect real positive change. This is just the first article of a short series about my experiences in Namibia, the Bushblok project, and eco-development as a whole. I hope you’ll stick around.

Related Reading

-

February 27, 2023

CCF: “Like No Other Place” -

October 25, 2016

A Return to CCF Namibia: Canada’s Support