Destroying an Apex Predator Can Kill an Ecosystem

-

- by Jameson Bowman November 4, 2018

Apex Predator in North America: The Grey Wolf and Lessons for Cheetah Survival

When Dr. Laurie Marker first arrived in Namibia (then South West Africa) in the late 1970’s she discovered that cheetahs were viewed as vermin and hundreds were being killed every year by farmers and ranchers. Between 1980 and 1991 there were 6,293 cheetahs reported killed by farmers in Namibia. Dr. Marker took an innovative and yet simple approach to the problem; she went door to door speaking to farmers asking why they were killing cheetahs. She discovered that conflict between humans and cheetahs was due predominantly to their potential, as an apex predator, to prey on the farmers’ livestock.

Many of the farms affected by cheetah depredation on livestock were very poor and rely heavily on a few livestock for their financial security, so the loss of even a single animal can be a disaster.

The local farmers’ sentiment likely would not have been surprising to Dr. Marker, who had gained her first experience working with wildlife in her native United States. The actions of the South West African farmers echoed her own country’s extirpation of the grey wolf half a century ago – this narrative has numerous parallels to the current plight of the cheetah.

Similar to the modern subsistence farmers of Namibia, the ranchers of 19th century United States were dependent on their livestock for their own survival. As American populations expanded they actively sought to rid their continent of competing predators and knowingly engaged in a centuries long war of extermination. Bobcats, wolves, coyotes, mountain lions and grizzly bears were all targeted for extermination but it was the wolf who was considered the most egregious predator of livestock depredation.

Starting from the mid 1800’s the federal government utilized trappers and paid bounties to encourage the eradication of wolves. So widespread was the condemnation and so determined were Americans to see them exterminated that in the very rural and wild state of 1899 Montana 23,575 wolves were killed in a single year. By the 1920s wolf populations had collapsed to such an extent that rarely more than a single wolf was killed per year, until 1926 when the last grey wolf was officially shot. Other than in Alaska and a small population in Michigan, which roamed between the American and Canadian border, Americans had won their war of extermination.

Yet almost immediately the effects of removing an apex predator and keystone species was felt throughout the Western States. Elk and deer populations ballooned out of control causing overgrazing and damage to the flora and fauna of their ecosystems. This caused widespread habitat loss and negatively affected the viability of populations of other species such as fish, birds and other mammals. Coyote populations which were originally confined to the western desert regions grew dramatically in the absence of their larger more aggressive cousin and spread across the continent even into Canada and Alaska.

In the 1990s grey wolves captured in western Canada were reintroduced into Yellowstone National Park. This highly controversial reintroduction has been heralded as a massive success for the park and its ecosystem. Environmentalists, wildlife activists, and park officials celebrate that the reintroduction of the apex predator has created a ‘trophic cascade’ where the reduced elk and deer populations, due to wolf predation, cause a trickledown effect in which the park’s flora have returned to larger and more populous volumes, rivers have become healthier resulting in more trout populations, and bird populations have returned and multiplied.

Even the reduction of coyote populations, again attributed to grey wolf predation, has led to increase in small mammal populations and a resurging beaver population. However, this positive ending is balanced out by other studies which suggest that after an absence of grey wolves for half a century the ecosystem has fundamentally changed in many ways and will never fully recover.

What can we learn from the American experience of the grey wolf for the plight of the cheetah? Similarly to the grey wolf, the cheetah is a top predator which plays an important role in maintaining wildlife populations within their ecosystem and as well, cheetahs have been ruthlessly persecuted by farmers who view them as a threat to their livestock.

It is imperative that the persecution of cheetahs by farmers and local communities stop or their extinction will be inevitable. Because of their role as apex predators, losing cheetahs would have a domino effect on the ecosystem. There is the added challenge for the cheetah; their very narrow genetic diversity makes them even more vulnerable to declining numbers. We must learn from our mistakes and help ensure they are not repeated throughout the world.

When Dr. Marker discovered the unofficial war on ‘vermin’ cheetah by talking with farmers she took the first steps in what would later become the driving mission of the CCF: that conservation strategies are only successful when they encompass working with and empowering local communities.

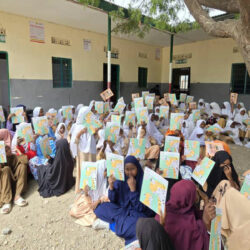

Today, CCF runs the Field Research and Education Centre and Model Farm which regularly hosts Namibian farmers to teach them modern agrarian and ranching techniques as well as to learn about Cheetahs, their benefit to the ecosystem, and how to live alongside them while maintaining healthy and profitable farms and ranches. Due to this on-the-ground and front-line approach the views of local farmers are changing but there is much more to be done.

To help support the preservation of cheetah populations, while building sustainable and prosperous African communities, please donate. In Canada, the charity is run by volunteers so that 98% of donations go directly to CCF Namibia.

Together we can learn from the mistakes of our past and ensure the survival of the cheetah in the wild.

Sources for this article.

Blakeslee, Nate. The Wolf: A True Story of Survival and Obsession in the West. Random House Canada: Toronto, 2017.

Dickman, Amy et al. “The Costs and Causes of Human-Cheetah Conflict on Livestock and Game Farms.” Cheetahs: Biology and Conservation. Ed. Marker, Laurie et al. Cambridge USE: Elsevier Inc. 2018. 173-189. Print.

Flores, Dan. Coyote America: A Natural and Supernatural History. Basic Books: New York, 2016.

Lackey, Katharine. Yellowstone’s Wolves Are back, But They Haven’t Restored The Park’s Ecosystem. Here’s Why. USA Today. September 7, 2018.

McCloskey, Erin. Wolves in Canada. Lone Pine: Edmonton, 2011.

Wildlife Conservation Network. Cheetah Conservation Fund, Spring Expo 2017, Dr. Laurie Marker, May 12 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-3OxnbLMOeE&t=1222s

Chadwick, Douglas H. “Wolf Wars: Once Protected, Now Hunted.”National Geographic. March 2010 vol. 217. NO.3 34-55. Print.

Beprovided Conservation Radio, Dr. Laurie Marker: Founder of Cheetah Conservation Fund. Nov 21 2017. http://beprovidedconservationradio.libsyn.com/dr-laurie-marker-founder-of-cheetah-conservation-fund

Faunographic. Episode 7: Big Cat Expert Dr. Laurie Marker Talks Cheetahs, September 10 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=3&v=p4BHLtygtog

TED. For more wonder, rewild the world. George Monbiot. September 9 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8rZzHkpyPkc

PBS Nature. Wolf Wars: America’s Campaign to Eradicate the Wolf. September 14, 2008.

Related Reading

-

November 9, 2023

Giving Tuesday Canada 2023 – Supporting Namibian Youth