About Cheetahs

The Cheetah’s Wild Life

There are three stages in the life cycle of the cheetah: cub (birth to 18 months), adolescence (18 to 24 months) and adult life (24 months and on).

The gestation (pregnancy) period for the cheetah is 93 days, and litters range in size from one or two up to six cubs (the occasional litter of eight cubs has been recorded, but it is rare). Cub mortality is higher in protected areas like national parks and wildlife reserves where proximity to large predators is greater than in non-protected areas. In such areas, the cheetah cub mortality can be as high as 90%.

Adult life for a cheetah in the wild is difficult. Cheetahs in the wild (both male and female combined) have an average age span of 10 – 12 years. The average lifespan of an adult male in the wild skews lower (8 years), due in part to territorial conflicts with competing groups of males. Adult mortality is one of the most significant limiting factors for the growth and survival of the wild cheetah population.

Physical Characteristics of Adult Cheetahs

Adult cheetahs’ weight averages between 75 and 125 pounds. They can measure from 40 to 60 inches in length, measured from the head to the hind quarters. The tail can add a further 24 to 32 inches bringing the total overall length up to 7.5 feet. On average, cheetahs stand 28 to 36 inches tall at the shoulder.

The cheetah is a sexually dimorphic species though it is difficult to identify cheetahs’ sex by appearance alone. Male cheetahs are slightly bigger than females and they have larger heads, but they do not display the same degree of physical difference between the sexes of other big cat species like lions.

Cheetahs have a thin frame with a narrow waist and deep chest. They have large nostrils that allow for increased oxygen intake. Cheetahs have a large lungs and hearts connected to a circulatory system with strong arteries and adrenals that work in tandem to circulate oxygen through their blood very efficiently.

With its long legs and very slender body, the cheetah is quite different from all other cats and is the only member of its genus, Acinonyx. The cheetah’s unique morphology and physiology allow it to attain the extreme speeds for which it’s famous.

Markings

The cheetah’s undercoat ranges in color from light tan to a deep gold and is marked by solid black spots. These spots are not open like the rosettes found on a leopard or jaguar’s coat, which is one way to quickly identify the cheetah.

Distinctive black tear stripes run from the eyes to the mouth. The stripes are thought to protect the eyes from the sun’s glare. It is believed that they have the same function as a rifle scope, helping cheetahs focus on their prey at a long distance range by minimizing the glare of the sun.

Cheetah tails end with a bushy tuft encircled by five or six dark rings. These markings provide them with excellent camouflage while hunting and make them more difficult for other predators to detect. The tail is also thought to be a signaling device, helping young cubs follow their mothers in tall grass. The tip of the tail varies in color from white to black among individuals.

Built for Speed

The cheetah is the world’s fastest land animal and Africa’s most endangered big cat. Uniquely adapted for speed, the cheetah is capable of reaching speeds greater than 110 kilometers per hour in just over three seconds. At top speed, their stride is seven meters long. The cheetah’s unique body structure: flexible spine, semi-retractable claws, long legs and tail allow it to achieve the unbelievable top speed of 110 km/hr (70 mph). The cheetah’s body is narrow and lightweight with long slender limbs. Specialized muscles allow for a greater swing to the limbs increasing acceleration.

Cheetahs’ foot pads are hard and less rounded than the other cats. The pads function like tire treads providing them with increased traction in fast, sharp turns. The short blunt claws, which are considered semi-retractable, are closer to that of a dog than of other cats. The claws work like the cleats of a track shoe to grip the ground for traction when running to help increase speed.

Fast and Flexible

The flexibility of the cheetah’s spine is unique. The cheetah’s long muscular tail works like a rudder, stabilizing, and acting as a counterbalance to its body weight. Swinging the tail back and forth continually adjusting to the movement of prey allows for sudden sharp turns during high speed chases. The cheetah’s shoulder blade does not attach to the collar bone, thus allowing the shoulders to move freely.

The hips pivot to allow the rear legs to stretch far apart when the body is fully extended. The hip and shoulder extension allows for a large range of extension during running, thus making both its exceptional stride length. The length between their steps is six to seven meters (21 ft) and four strides are completed per second. There are two times in one stride when the cheetah’s body is completely off the ground: once when all four legs are extended and once when all four legs are bunched under the body.

Cheetah Cubs

At birth, the cubs weigh 8.5 to 15 ounces and are blind and helpless. Their mother will groom them patiently, purring quietly and providing them warmth and security. After a day or so, the mother will leave the cubs to hunt for herself, so she can continue to care for the cubs. This is the most vulnerable time for the cubs, as they are left unprotected. They will live in a secluded nest until they are about six to eight weeks old, being regularly moved by their mother from nest to nest to avoid detection by predators. The mother will care for her cubs on her own for the next year and a half.

At about six weeks of age

The cubs begin following their mother on her daily travels as she is looking for prey. During these first few months she cannot move far or fast and cub mortality is highest. Fewer than one in 10 cubs will survive during this time, as they perish from predation by other large predators such as lions and hyenas, or from injuries. This is the time when life skills are taught.

Cheetah cubs have a thick silvery-grey mantle down their back. The mantle helps camouflage the cubs by imitating the look of an aggressive animal called a honey badger. This mimicry may help deter predators such as lions, hyenas, and eagles from attempting to kill them. Cubs lose their mantle at about three months of age.

Between four to six months of age

Cheetah cubs are very active and playful. Trees provide good observation points and allow for development of skills in balancing. The cubs’ semi non-retractable claws are sharper at this age and help them grip the tall ‘playtrees’ they climb with their siblings. Learning to hunt is the most critical survival skill that the cubs will develop. At one year of age, cheetah cubs participate in hunts with their mother.

At about 18 months of age

The mother and cubs will finally separate. Although not fully adept at hunting on their own, independent male and female cubs will stick together for a few more months to master their hunting skills. When the adolescent females begin cycling, dominant males will court them and drive their brothers away.

Male Coalitions

As the female siblings become sexually mature they will split from the group to lead a largely independent life. Male siblings remain together for the rest of their lives, forming a group known as a coalition. Coalitions increase hunting success and act as a defense against other predators.

When the split from sisters occurs, the males will roam until they can find and defend a territory. This process can take a few years and males may travel hundreds of miles, being moved out of one area to another, pushed on by more experienced male coalitions. Eventually, the group will find a place where they can settle. This will become the coalition’s territory and could span 15 to 30 square miles.

Cheetahs that become orphaned at a young age, and are brought into a rehabilitation situation, can be paired with non-related individuals to form a coalition. When these cheetahs are released back into the wild, the created coalitions will often remain intact throughout the life of the individuals.

Mating

Females lead solitary lives unless they are accompanied by their cubs. Unlike male cheetahs that prefer to live in set territories with their coalition, females travel within “home ranges” that overlap multiple male groups’ territories. Female cheetah home ranges depend on the distribution of prey. If prey is roaming and widespread, females will have larger ranges.

Estrus in female cheetahs is not predictable or regular. This is one of the reasons why it is difficult to breed cheetahs in captivity. Mating receptivity depends on environmental factors that, researchers have found, are triggered by the proximity of males and their scent markings. Estrus lasts up to 14 days and females will mate with multiple males during this time period. Male cheetahs that encounter a female cheetah in estrus will stay with her and mate up to three days and at intervals throughout the day. When it comes to mating, there are no dominant males within the coalition that claim exclusive access to females. All males within a coalition will mate.

Genetic Diversity

During the last Ice Age the world’s population of cheetahs plummeted to just a handful of individuals. This event caused an extreme reduction of the cheetah’s genetic diversity, known as a population bottleneck, resulting in the physical homogeneity of the species’ current population. Cheetahs are so genetically similar that in experiments, reciprocal skin grafts from unrelated cheetahs were accepted by the other’s immune system due to the animals having similar major histocompatibility complex (MHC) genotypes.

Researchers have discovered that suitable levels of genetic diversity are vital to any population’s ability to adapt and overcome environmental changes and unexpected disasters. Unsustainable human expansion and irresponsible consumption can cause pressure on ecosystems worldwide. Population research has shown that when habitat is destroyed and populations become fragmented and isolated, the rate of inbreeding increases and the genetic diversity lowers.

Physiological impairments such as: poor sperm quality, focal palatine erosion, susceptibility to infectious diseases, and kinked tails are a result of low genetic diversity within both the wild and captive cheetah population.

Hunting

Cheetahs are visual hunters. Unlike other big cats cheetahs are diurnal, meaning they hunt in early morning and late afternoon. Cheetahs climb ‘playtrees’ or termite mounds to get an optimal vantage point for spotting prey against the horizon. The hunt has several components. It includes prey detection, stalking, the chase, tripping (or prey capture), and killing by means of a suffocation bite to the throat.

Diet and Eating

The prey species on which the cheetah depends have evolved speed and avoidance techniques that can keep them just out of reach. Cheetahs prey includes: gazelles (especially Thomson’s gazelles), impalas and other small to medium-sized antelopes, hares, birds, and rodents. Cheetahs will also prey on the calves of larger herd animals.

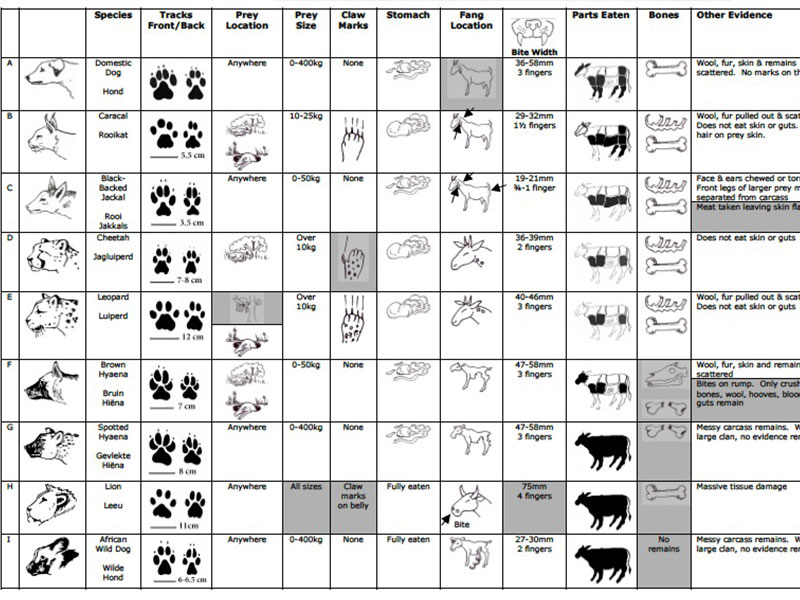

Cheetahs generally prefer to prey upon wild species and avoid hunting domestic livestock. The exception happening in sick, injured and either old or young and inexperienced cheetahs. Generally, the livestock animals that are lost to predation by cheetahs are also sick, injured and old/young. Keeping livestock in kraals and utilizing non-lethal means of protection can dramatically reduce livestock predation.

Activity

While cheetahs can reach remarkable speeds, they cannot sustain a high speed chase for very long. They must catch their prey in 30 seconds or less as they cannot maintain maximum speeds for much longer. Cheetahs spend most of their time sleeping and they are minimally active during the hottest portions of the day. They prefer shady spots and will sleep under the protection of large shady trees. Cheetahs do not hunt at night, they are most active during the morning and evening hours.

Role in the Ecosystem

The cheetah serves a special role in its ecosystem. Cheetahs are one of the most successful hunters on the savanna but their kills are very often stolen by larger carnivores or predators that hunt in groups. Predators play an important role in any ecosystem. They keep prey species healthy by killing the weak and old individuals. They also act as a population check which helps plants-life by preventing overgrazing. Without predators like the cheetah, the savanna ecosystem in Namibia would be very different and the current ecological trend toward desertification would be accelerated.

Vocalizations

Unlike other “big cats”, a classification that includes: lions, tigers, leopards, and jaguars) cheetahs don’t roar. They growl when facing danger, and they vocalize with sounds more equivalent to a high-pitched chirp or bubble and they bark when communicating with each other. The cheetah can also purr while both inhaling and exhaling.

Purring

Moan/Spit

Chirping

Growling

Growl/Chirp

Species Then and Now

Relatives of the modern cheetah had worldwide distribution until about 20,000 years ago, when the world’s environment underwent dramatic changes during the Great Ice Age. Only a handful of individuals remained.

The population of cheetahs rebounded. Up until ~10,000 years ago their range spread across the entire African continent (minus the Congo Basin and the Sahara Desert) and into Asia from the Arabian Peninsula to eastern India. Today, cheetahs are found in only 9% of their historic range and are functionally extinct. Once found throughout Asia and Africa, today there are fewer than 7,100 adult and adolescent cheetahs in the wild.

Protected Status

Currently, cheetahs are listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. In Namibia, they are a protected species. Under the Endangered Species Act in the United States, they are considered Endangered. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) lists them as an Appendix 1 species. Most wild cheetahs exist in fragmented populations in pockets of Africa, occupying a mere 9 percent of their historic range. In Iran, fewer than 50 Asiatic cheetahs (a sub-species) remain.

The largest single population of cheetahs occupies a six-country polygon that spans Namibia, Botswana, South Africa, Angola, Mozambique and Zambia. Namibia has the largest number of individuals of any country, earning it the nickname, “The Cheetah Capital of the World.” More than 75 percent of remaining wild cheetahs live on rural farmlands alongside human communities.

Cheetahs in Captivity

In captivity cheetahs can live from 17 – 20 years. In countries across Africa, like Namibia, it is illegal to capture and take live cheetahs from the wild. Also in the majority of African countries, like Namibia, it is illegal to keep cheetahs under private ownership or as pets. Cheetah Conservation Fund and other Africa-based NGOs keep populations of injured or orphaned animals in captivity as part of rehabilitation and rewilding efforts.

Suitability for release is dependent on:

- the age of the individuals when they became orphaned

- the degree to which human intervention was required for their survival

Very young and extremely ill animals will have greater degrees of contact with human caretakers. Survival in the wild depends on an aversion to humans and avoidance of human populations. Cheetahs that require hand-rearing and prolonged medical treatment do not possess an adequate fear of humans for life in the wild, especially when their territories are increasingly likely to be shared by human settlements.

Zoos and Conservation

Accredited zoos around the world participate in captive breeding programs that track the genetic suitability for mating pairs. Accreditation criteria differs between accrediting organizations. Accreditation in most cases requires that zoos holding captive cheetahs must support conservation work. Cheetah Conservation Fund lists the zoos that fund our conservation work here.

Cheetah Conservation Fund manages the International Cheetah Studbook for captive cheetah populations.

Specialized Conservation Needs

As with all other species fighting extinction, the problem facing the cheetah is complex and multifaceted. However, most of the reasons for the cheetah’s endangerment can be grouped into three overarching categories:

- human-wildlife conflict,

- loss of habitat and loss of prey,

- poaching and illegal wildlife trafficking, with cubs being taken from the Horn of Africa and smuggled into the exotic pet trade, primarily in the Gulf States.

Human-Wildlife Conflict

Unlike other large cats and pack predators, cheetahs do not do well in wildlife reserves. These areas normally contain high densities of other larger predators like the lion, leopard, and hyena. Predators such as these, compete with cheetahs for prey and will even kill cheetahs given the opportunity. In such areas, the cheetah cub mortality can be as high as 90%. Therefore, roughly 90% of cheetahs in Africa live outside of protected lands on private farmlands and thus often come into conflict with people.

When a predator threatens a farmer’s livestock, they also threaten the farmer’s livelihood. Farmers act quickly to protect their resources, often trapping or shooting the cheetah. Because cheetahs hunt more during the day, they are seen more often than the nocturnal predators which contributes to a higher rate of persecution on the cheetah.

Human-wildlife conflict

Learn more about CCF’s efforts to mitigate human-wildlife conflict

Habitat Loss

Cheetahs require vast expanses of land with suitable prey, water, and cover sources to survive. As wild lands are destroyed and fragmented by the human expansion occurring all over the world, the cheetah’s available habitat is also destroyed. Available habitat is fragmented, and degraded reducing the number of animals an area can support. Numerous landscapes across Africa that could once support thousands of cheetahs now struggle to support just a handful.

Illegal Wildlife Trade

In many parts of the world there are strong cultural associations to keeping cheetahs as companions. There is a long history of the practice and it is commonly seen in ancient art.

In contemporary times, cheetahs are still viewed as status symbols. Though cheetah ownership and exotic pet ownership has been outlawed in many countries, there is still a high demand for cheetahs as pets. Cubs are illegally captured from the wild and only one in six survives the journey to a potential buyer.

Illegal Wildlife Trade

Learn more about CCF’s efforts to end the illegal trade in cheetahs across the species range.